“You can't stay in your corner of the forest waiting for others to come to you. You have to go to them sometimes.” — Winnie the Pooh

MIT neuroscientists have now shown that they can influence those judgments by interfering with activity in a specific brain region--a finding that helps reveal how the brain constructs morality. In the new study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers used a magnetic field to disrupt activity in the right temporoparietal junction (TPJ). The stimulation appeared to influence subsequent judgments that required an understanding of other people's intentions.

The findings offer "striking evidence" that the right TPJ, located at the brain's surface above and behind the right ear, is critical for making moral judgments, says Liane Young, the paper's lead author and a postdoctoral associate in brain and cognitive sciences. It's also startling, since normally people are very confident and consistent in such judgments, she adds. "You think of morality as being a really high-level behavior," Young says. "To be able to apply [a magnetic field] to a specific brain region and change people's moral judgments is really astonishing."

The Wall Street Journal just reported that the Federal Communications Commission is holding "closed-door meetings" with industry to broker a deal on Net Neutrality -- the rule that lets users determine their own Internet experience.

Given that the corporations at the table all profit from gaining control over information, the outcome won't be pretty.

The meetings include a small group of industry lobbyists representing the likes of AT&T, Verizon, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association, and Google. They reportedly met for two-and-a-half hours on Monday morning and will convene another meeting today. The goal according to insiders is to "reach consensus" on rules of the road for the Internet.

This is what a failed democracy looks like: After years of avid public support for Net Neutrality - involving millions of people from across the political spectrum - the federal regulator quietly huddles with industry lobbyists to eliminate basic protections and serve Wall Street's bottom line.

Mr. Musk is a member of the PayPal Mafia — those serial entrepreneurs who, for a time, looked like the Brat Pack of the Valley. He made a fortune as a co-founder of PayPal, the e-commerce payments system. Not so long ago, he had more than $200 million in cash. Not bad for 38.

Now Mr. Musk says his account is empty. Actually, less than empty. He says he invested his last cent in his businesses and is living off loans from his wealthy friends. He subsists, according to court filings, on $200,000 a month and still flies his private jet.

“About four months ago, I ran out of cash,” Mr. Musk acknowledged.

It was quite a revelation, one that laid bare an uncomfortable truth in the world of venture capital: high-tech entrepreneurs who look rich are often relatively cash-poor, at least next to their glittering images. Mark Zuckerberg may be a billionaire when, or if, Facebook goes public. Larry Ellison, the founder of Oracle, lives like a king. But most of his wealth is tied up in Oracle stock. Mr. Ellison lives in part off loans.

People like Mr. Musk may have redefined what it means to be rich, particularly young and rich. But somehow, many of these seemingly successful people live on the financial edge, waiting, hoping for the next deal to unlock their next fortune.

Mr. Musk told me in an interview that he put his last $35 million into Tesla, which only two years ago was on the edge of bankruptcy. That depleted virtually all his “cash reserves.” “That was my choice,” he insisted.

Faced with what he characterized as “liquidity issues,” he said: “I could have either done a rushed private stock sale or borrowed money from friends.” He chose to hang onto his stake.

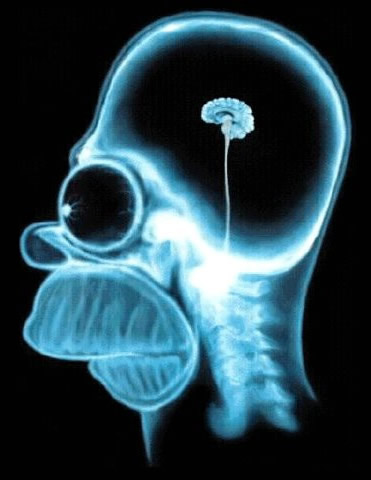

The average human’s resting heat dissipation is something like 2000 kilocalories per day. Making a rough approximation, assume the brain dissipates 1/10 of this; 200 kilocals per day. That works out (you do the math) to 9.5 joules per second. This puts an upper limit on how much the brain can calculate, assuming it is an irreversible computer: 5 *10^19 64 bit ops per second.

Considering all the noise various people make over theories of consciousness and artificial intelligence, this seems to me a pretty important number to keep track of. Assuming a 3Ghz pentium is actually doing 3 billion calculations per second (it can’t), it is about 17 billion times less powerful than the upper bound on a human brain. Even if brains are computationally only 1/1000 of their theoretical efficiency, computers need to get 17 million times quicker to beat a brain.

The model of the Antikythera mechanism shown here is one of the clearer I've seen. I'm fascinated by analog computers, but figure we need an entirely new category for "organic" models.